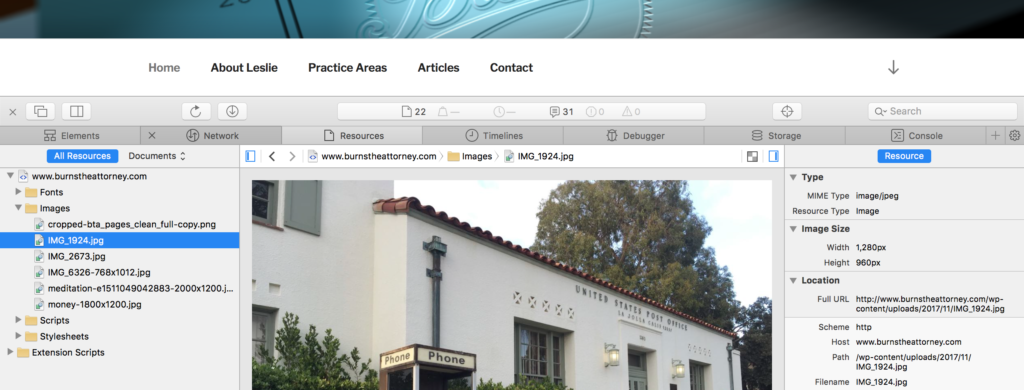

The photo is of the sourdough boules I made last week. They are from scratch, from a starter I started months ago, and comprising nothing more than flour, water, and salt, including the starter.

I bake almost every week, never less than every-other week, and it has been a couple of months since we’ve purchased bread of any kind, except for hamburger buns once when we had a last-minute guest to dinner and I didn’t have time. It takes me all day to make the dough and shape the boules, which then have a final proof overnight and get baked the following day. It is a discipline and, for me, an exercise in mindfulness, presence, and perseverance.

I grew up cooking. I literally cannot remember a time when I didn’t cook. My mother was a gender traditionalist and, being the only daughter, it didn’t matter that I was substantially younger than my brothers–I had to cook for them, first with her then on my own, later. From my very beginning of my own consciousness, I remember being in the kitchen or the grocery. I actually have (and often use) the cast-iron flat small oval pan I remember trying to make pancakes on, by myself for the first time, when I could not have been more than five [1].

Mom was a very good cook and so am I, and I (like her) cook intuitively rather than by following recipes (see “there is fat in the batter” thinking in FN1… ha!). When my brother took cooking lessons as an adult he asked for my recipes and I could not give him more than a rough “some of this, a bit of that” kind of litany. Honestly, I don’t know how I make a lot of what I make–I just make it.

I’m one of those people who can look in a fridge and cupboards and, no matter how bare, will be able to come up with a couple of tasty “peasant food” meals. I learned this ability from Mom, and our poverty. It was a great tool for surviving college, grad school, and law school.

Anyway, Mom, for all her cooking, didn’t bake much and so neither did I. Basic cakes, yes, and the occasional cookie, but those are pretty forgiving if you stray from the recipes. Breads, though, require a certain scientific discipline she never could (or, perhaps, would choose to) grasp. I think some of it was because her mother was such a good baker that, just to be difficult, Mom chose not to follow Grandma’s baking tradition. My very Polish grandmother would rarely appear from the east (Wheeling, WV–we lived in Columbus, OH) but, when she did, it was always with paper grocery bags filled with enriched, yeasty, often raisin-filled, tasty baked goods. I can still remember the smell of her and it’s the smell of the goods in those bags. Sadly, we never baked together and thus bread making was fairly foreign to me. I wanted to learn so I did, later in life.

Cooking is like shooting photography–you can play a lot with and stray a lot from the recipe and still get good (sometimes great) results. Baking however, especially bread, is like traditional photo printing in the darkroom–you have to mix hard science with the art and if you stray too far from the science, you get crap results. In other words, you need to understand and respect the science of bread-making (yeast, heat, gluten formation, proteins, etc.) in order to make decent bread and to learn the science to the point of mastery to make really good bread.

For me, baking bread well is also like being a good lawyer: the more you learn about your particular field of law, the better you create. You have to respect the traditions, statutes, rules, and the processes, but you’ll make better lawyering when you have internalized how the law works so, for example, you can know the feel of that right spot in any of your drafting. Just as a Tartine sourdough loaf is to Wonderbread, so is a beautifully crafted document to a boilerplate one. When you know the specific law in real depth, you can find the hidden issues in a case and the winning legal points. It’s like learning how bread dough feels when it’s been worked enough or proofed right.

So why am I sharing all this? Because I think there is a lot of Wonderbread in my profession, especially in copyright law these days. I want you to know that is not what you’ll get with me. There are large firms who have a gazillion associates and paralegals who will take your case and treat it like it’s debt collection. They don’t know any more than the minimum about the law; they are competent, not obsessed. I’ve read the complaints and other papers they file and I don’t know how some of them can look at themselves in the mirror and call themselves “good lawyers.” I can tell you there has been more than one where I feared the client would get stuck with paying the other side’s attorney’s fees because the case should never have been filed.

Moreover, these massive firms won’t care why this particular image means more to you than another or look at the case in any depth, they’ll just do the minimum to get something and often not even remember your name. Worse, there are companies not owned or run by lawyers and so they care first and foremost about making their own bank, not you or your case. But they’ll be happy to take about half, if not more, of your settlement for their efforts.

That ain’t me. I know and care deeply about the law and how it works. I’m a dweeb, a nerd; I read case law and journals not because I have to but because I love it. I’m a passionate lawyer and obsessively so about copyright law. I agonize over my drafting, the rules, and making sure the law I cite is the best for the issue. I file only a few cases at any one time because litigation is time-intensive and I refuse to take on more and maybe do any less well.

Also, I build relationships with my clients and I take pride in that. I know about their families and they know about me and those close to me. I know the history of the works they ask me to protect, whether that is a work made for a client or personal work, and why it matters. While I get paid (usually much less than the infringement mill companies, by the way), I also sometimes get gifts from my clients–usually their own art–and that is something that has brought me to tears more than once.

If you want Wonderbread, I suppose you may be satisfied with the big firms or infringement “enforcement” companies. You wouldn’t be a good client for me, then. But if you want a relationship with a lawyer–something more than just a form and a rotating list of associates for your cases–shoot me an email and let’s get to know each other.

You might even a bread recipe out of it.

Really good bread.

___________________________

[1] Sadly, they were a bit of a fail as couldn’t remember if you needed to grease the pan and I errantly decided that, since there was fat in the batter, I didn’t need to. Mom came in as I was trying to scrape off the first batch.