The Copyright Claims Board, aka the CCB or copyright small claims, launched today. You can now file claims using that system, rather than federal court.

However, that doesn’t mean you must use that system. I’ve written about my reservations, but that’s not what I’m talking about here. Rather, I mean that just because the CCB is now available as an option doesn’t mean that you should skip the step of trying to work out an infringement matter without filing anywhere first. My legal philosophy is that one should always try first to work things out without litigation, be that in federal court or the CCB.

In the past, an infringement of an untimely or unregistered work (without a CMI removal claim) was almost assuredly going to be a “can’t take that on contingency” situation for me. Now, however, I’ll be taking a different look at those kinds of matters.

The existence of the CCB system gives those of you who have not timely registered your work a new tool to use in pre-litigation negotiations. Instead of having to prove up a license rate to an infringer (“actual damages”), now you can say “Hey, if we go through the CCB, I can be awarded up to $7500 in statutory damages for this infringement” which gives you some negotiating leverage. Of course, you shouldn’t ask for the full $7500 to settle–that is rather defeating the purpose of pre-litigation settlement (i.e., to save everyone time, effort, and money), but it lets the other side know what they might be facing if you don’t work it out.

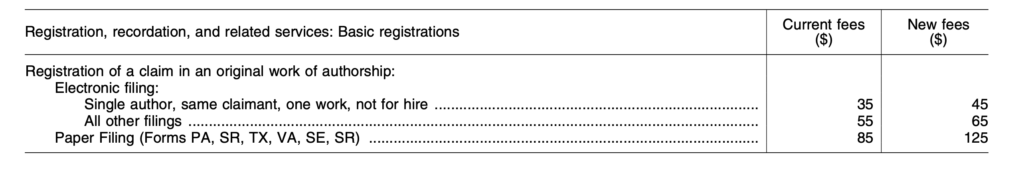

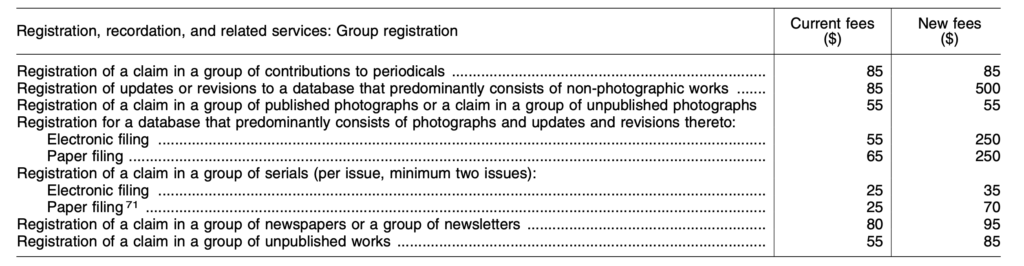

Also, remember that you will have to register the work before you can get a judgment from the CCB; that is, you need to have applied for registration prior to filing the claim and you need your certificate before the process is completed (there are ways to expedite registration, if needed). If you haven’t applied for a registration of an infringed work yet, you might be able to use that to help convince the other side to settle because you can settle for less money now. I mean, if you have to register and pay the filing fees, etc., you’ll have to get more to settle–that’s basic business math.

Sadly, however, a well informed opponent will know that they can opt out of any CCB proceeding brought against them, reducing you to actual damages again, but lots of infringers are not going to be so informed. And you don’t need to inform them.

Note, I am NOT suggesting you lie to any opposing party–you shouldn’t say they’ll “have no option but fight the claim in the CCB” or similar, but you can say, “If I bring this claim in the CCB, I can be awarded up to $7500 in statutory damages.” There is no lie there. What I’m saying is that you don’t have an obligation to tell them how the CCB works for defendants and that they have an out, not until you actually file with the CCB. If you end up filing in the CCB, then you have a duty to inform the opposing party about the claim and their options. Until you file, though, nope.

Anyway, as I said, if you have an infringement of a non/untimely registered work, now I may be able to help you on contingency or a hybrid fee. You can submit the information for my review using the form, here, and I’ll let you know what your options are, including what fee arrangements are available. As I mentioned in my previous post, I am limited annually to the number of claims I can file for my clients, so I will have to pick and choose a bit if we get to that point. But, we might work together to try to get you a reasonable settlement before taking that CCB filing step.