(I first wrote about this many, many years ago, but today feels like a good day to share this story again)

Several years ago, the wife of the photographer who got me into the photo biz (the fabulous Stephen Webster) bought him the at-the-time newly (re)released original Planet of the Apes movies, which he desperately wanted, for a birthday present. She wanted to surprise him with it at a dinner they were going to have, with another couple, in a nice restaurant. The surprise wasn’t just the gift– it was that someone in a gorilla suit would deliver it during the meal. Sadly, she told me on the phone as we gabbed about the impending birthday, waiting for her husband to get out of the darkroom, the person she had lined up had bailed.

I immediately volunteered! I thought it was a great idea and she seemed stuck so, I thought, why not. It wasn’t until after I hung up that I thought, “Oh hell, what have I just agreed to do?! I’m going to look an idiot…”

Then, I thought some more and the old saying “in for a penny, in for a pound” popped in my head. I decided I would be the best gorilla I could be.

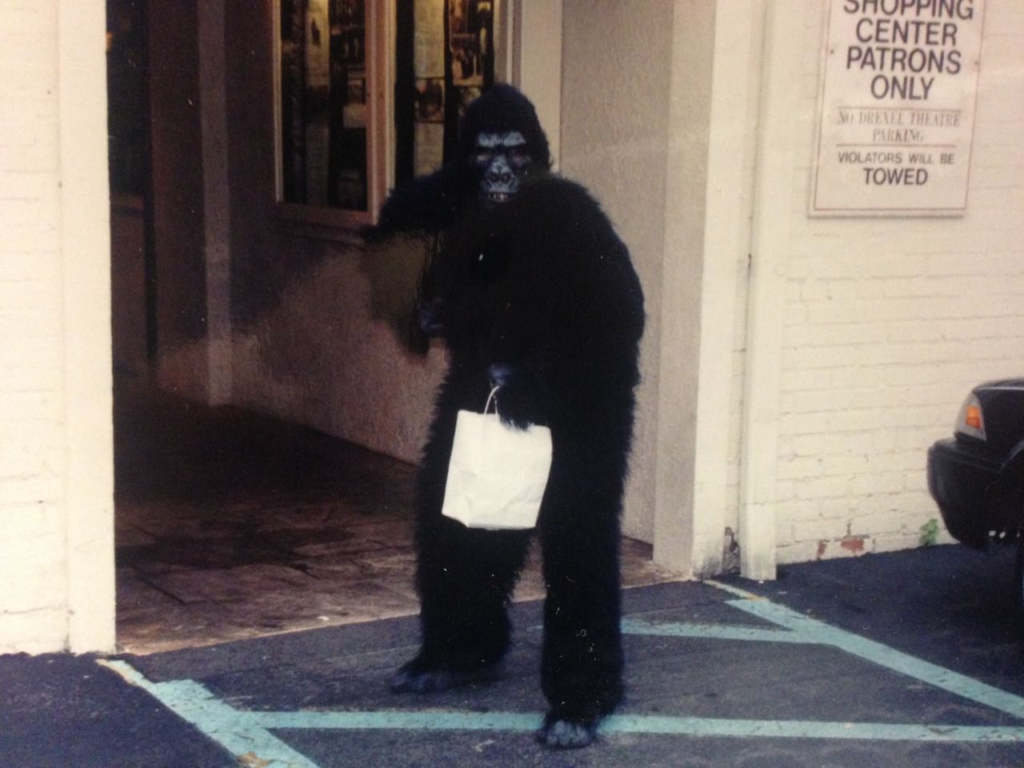

On the appointed day, I parked my car, put on that gorilla suit (I had already blacked out around my eyes to make sure he wouldn’t recognize me) grabbed the gift bag, and headed out.

On a Saturday evening, in mid-July Columbus, Ohio heat and humidity, I gorilla’ed down a crowded neighborhood sidewalk, making ape noises at random people. I gorilla’ed into the restaurant, right past the maitre d’ (at whom I gorilla-hooted), and found the foursome.

Then the fun really started. I abused the poor victim and his wife and the other couple… but especially him. I pulled his hair, sniffed bits, put my fingers into his food, made lots of ape-ish noises, and even threw bread. Then, as magnificently as I could, I chucked the gift at the honoree, made very excited ape noises while beating my chest, and left, still gorilla-ing all the way back to my car, unrevealed.

The people in the place had laughed and stared and everyone had a great time. This was before ubiquitous cell phones so there are few photos and no videos, but the crowd seemed entertained.

The next Monday, at the studio, Steve excitedly told me the story of what had happened. He said how amazing the ape had been, how the person really pulled it off, and most of all that he couldn’t figure out who it was! I totally played along for hours.

He was stunned when, eventually, he found out it had been me. If I remember correctly, I had to make ape noises before he got it.

Why am I sharing this story? Because I was completely liberated by that suit. I could never imagine doing half what I did in my regular clothes, but wearing the costume, I could be the ape. Every time I have to do something I haven’t done before, as a lawyer, I remember putting on the gorilla suit.

I encourage you to do the same in your business. Play the role of the fabulous artist. Next time you have a one-on-one new client meeting or event where you might meet potential clients, wear fabulous clothes you wouldn’t normally wear, but that you imagine your professional hero would wear. Just go with it. Pretend you have confidence. Do this especially if you are normally shy and self-deprecating. Pretend you are everything you want to be. Just have fun with it.

As others have said, fake it until you make it. Don’t fake your creative work, of course, but do fake the personal image and the confidence. Wear a costume and play the role. At worst, you’ll have fun. At best, you’ll get a project and be one big step closer to making real the imaginary person you were portraying.